1. Introduction

wkward posture is a considerable deviation from the neutral position of one or combination of joints (Pinzke and Kopp, 2001). According to Westgaard and Aaras (1984), these postures typically include reaching behind, twisting, working ahead, wrist bending, kneeling, stooping, forward and backward bending, and squatting. It was further stated that such postures are related to injuries that are incurred during tasks that are static in nature, long lasting and that demand exertion of force.

It is documented that there is a relationship between awkward postures and pain (Grandjean and Hunting, 1977). Awkward postures combined with heavy physical workload result in a high frequency of Work related Musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) (Pinke and Kopp, 2001). Body postures determine which joints and muscles are used in an activity and the amount of force or stresses generated (Putz-Anderson, 1998). According to Kerst (2003), extreme postures, combined with force and frequency, will cause damage more quickly than when the postures are more natural or neutral.

The increase in concerns for ergonomics issues in the workplace is well founded; as it is related to work, working position; the suitability of instruments to the physical and physiological characteristics of the workers, psychological factors and environmental conditions which may affect workplaces and affect the health of the workers (Bazroy, et.al., 2003;Ajimotokan, 2008).

The amount of fatigue experienced depends largely on the posture of the performer. Many of the conditions of musculoskeletal disorders could be prevented if the amount of awkward, heavy, repetitive activities required by the job is reduced (OSHA's 1999).

OWAS has been shown to be easy to use in analyzing a wide range of different postures and a suitable tool in analyzing construction jobs. The basic OWAS records the postures of the back, arms and legs (Mattila, et.al., 1993: Karhu et.al., 1981). Kivi and Mattila (1991) and Mattila et al. (1993) analyzed the working postures of construction workers using OWAS method. Their studies indicated that OWAS was a suitable, reliable and practical method for analyzing construction jobs. Lee and Han (2013) used OWAS to analyze the working postures of construction workers on building the foundations of a log cabin. The study discovered workers exhibited poor working posture. Thomas et al., 2007, measured the prevalence of low back pain among 94 residential carpenters using OWAS to measure elements of postures. Slight risk for injury was found in 10 jobs-tasks while distinct risk was found in 7 of the 10 jobs-tasks. The weight carried by workers in brick making factories and positions taken in their daily task were measured using OWAS method and it was concluded that the method is imperative for ergonomics recommendations for minimization or eradication of suffering injury and worker's postural constraints (Pandey and Vats, 2012). Mattila et al., (1993) applied OWAS method to identify the most problematic postures among 18 construction workers in hammering task performed at building construction site to reduce postural load of dynamic hammering tasks. It was concluded that the method proved to be very useful.

The manner in which construction activities are executed adversely affects the health of construction Several studies have quantified the benefits that accrue from health and safety training (Jannadi and Al-Sudairi, 1995;Lingard & Rowlinson, 2005) and also confirmed positive correlation between health and safety training and health and safety performance (Rowlinson, 2004;Smallwood, 2006). The trade specific research conducted among bricklayers, plasterers, painters, and their respective assistants suggested a range of interventions that could contribute to an improvement in construction ergonomics one of which included ergonomics training of workers (Samuels et al., 2006). According to Bellis (2007), the goal of ergonomics training in the workplace is to prevent injuries and illnesses by reducing or eliminating worker's exposure to occupational hazards.

The aim of this study is to evaluate workers' postural behaviours at manual material lifting tasks among construction workers. The objectives of the study are; a) to compare the contributions of body movement at work to WMSDs b) to ascertain the level of ergonomics training, its acceptability among the group of workers and its impacts on work methods.

2. II.

3. Material and Methods

Work place analyses were accomplished by observing the tasks and watching the workers as they were carrying out the manual lifting tasks. An instantaneous observation of the postures and video recording were made which was later played indoor and observed by two ergonomics experts drawn from academics. The OWAS data was analyzed with WinOWAS software, a computerized system for the analysis of work postures. Four-digit code representing the back (four choices), three arm postures, and seven leg postures were used. The use of the weight of loads handled was classified by a three-class scale (as shown in table 1). Postures were recorded for each of the work phase during the working periods and within 30 seconds.

A total of eight hundred and forty-four (844) working postures were recorded and analyzed (four hundred and twenty two (422) for each category of workers). For OWAS method and as adopted in this study, AF2 (Action family 2) are grouped postures that required actions in the nearest future), AF3 are grouped postures that required remedial actions very soon), and AF4 are grouped postures that required immediate remedial actions).

4. Table 1 : OWAS posture code definitions

Questionnaires were conducted through interviews for 250 healthy male workers to identify the musculoskeletal symptoms among the workers. Level of ergonomics information readily made available, its approval among the group of workers and its impacts on their daily lifting tasks methods were also verified.

5. III.

6. Result and Discussion

Table 1 shows the OWAS code of AF3 and AF4 postures recorded for each category of jobs studied.

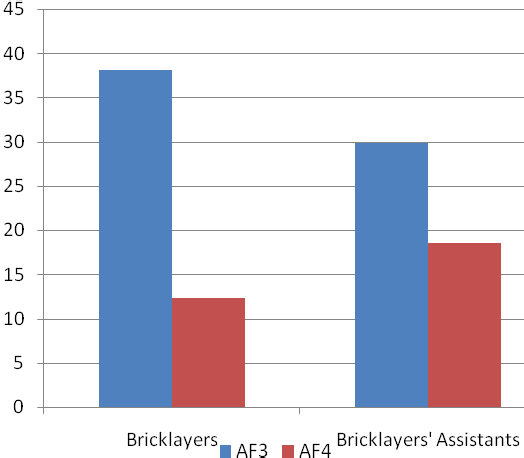

A total number of 417 harmful postures representing about forty-nine percent (49.4%) which included 161 and 126 postures for Bricklayers and Bricklayers' Assistants respectively in the group of AF3 and 130 postures (15.4%) involving 52 and 78 postures in the categories of BL and BA respectively for AF4 family were reported (Figure 1).

Close to thirty percent (30%) of BA and about thirty-eight percent (38%) of BL recorded postures fall into the family of AF3. In the family of AF4, about nineteen percent (18.5%) of postures in BA group was reported while approximately twelve percent (12%) of BL postures fall into this category (Fig. 2).

7. B Back

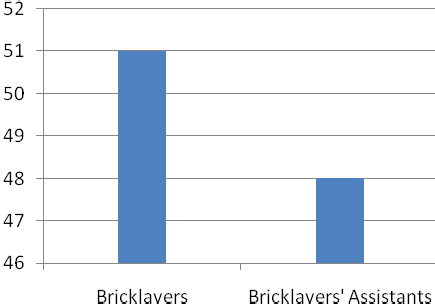

Arms Legs Load/Use of Force Comparing the two jobs (Figure 3), an average of fifty-one percent (51%) postures of workers in BL category and forty-eight percent (48%) postures of the workers in BA group required either soon or immediate remedial actions and ergonomics redesign to reduce the effect of harmful postures. The awkward postures adopted by the workers' may have contributed to the various reported body pains as observed by more than sixty percent (60%) of the workers responses on the two categories of jobs in the last month and 7days of the study time (Figure 4). One way to reduce the effect created by AF3 and AF4 codes is to minimize the angle of asymmetric; by lifting the load directly from the front thereby maintaining natural postures.

8. Conclusion

Twisting and bending of body parts are so frequent in the manual lifting jobs. Prolonged bending of back while lifting block/mortar from the sides was identified as most strenuous postures in the course of performing the tasks.

Meanwhile, health hazards are hardly considered by the group of workers. Majority of them had no regular ergonomics training as regarding safe postures. Not many of the trained ones put it into practice while many are still ignorant of the benefits for such change in work methods/habits. The few workers who adopted the training found it secured.

However, the level of ergonomics information made available to the group of workers needs some improvement. Physical demonstration/training on how and the best way to maintain natural postures at manual lifting related task are very necessary most especially in construction trades. Workers also need to be sensitized on the short and long time health implications of working in harmful postures.

| A AF3 POSTURES | AF4 POSTURES | ||||||

| BRICKLAYERS | BRICKLAYER | BRICKLAYERS | BRICKLAYER | ||||

| ASSISTANTS | ASSISTANTS | ||||||

| CODE | FREQ. CODE FREQ. CODE | FREQ. | CODE | FREQ. | |||

| 2142 | 52 | 2153 | 63 | 4141 | 18 | ||

| 3143 | 32 | 2143 | 32 | 4142 | 13 | ||

| 2141 | 33 | 1343 | 31 | 4143 | 12 | ||

| 2142 | 28 | 3242 | 9 | ||||

| 3142 2113 | 10 3 | ||||||

| 2133 | 3 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 161 | 126 | 52 | 78 | |||